The printing industry is not always good at honouring its past: the inventions, processes, products or the people. That is a pity because it is the men and women of the past that have brought the industry to where it is today, just as it is the individuals of today who will shape the printing industry of tomorrow. We do not move forward in isolation, today we build on what happened yesterday and we have much cause to give thanks to our forerunners.

Compiling a top 20 of great British printers is an impossible task. There are so many names that should appear on these pages but do not. And what makes a printer ‘great’ anyway? There is no definitive answer to the question, but all the men and women in this list have all made their unique contributions to their trade and each one is certainly great.

William Caxton, 1420–1491

Printer, Westminster, London

Printing from movable type only reached England 25 years after the first books had been printed in Germany. England was, however, the only country in Europe where the pioneer of the process was a native. William Caxton – a middle-aged amateur with a background in the woollen trade – came to printing in 1471 when he translated Lefèvre’s Recueil des histories de Troye, which he printed himself having first observed the craft in Cologne. Back in England he set up a press in the precincts of Westminster Abbey, secured a royal warrant, and in 1477 issued the first book printed in this country. Although he specialised in expensive, publications he was not England’s best printer, but he was certainly the first. Caxton is immortalised in a stained-glass window at Stationers' Hall.

Printing from movable type only reached England 25 years after the first books had been printed in Germany. England was, however, the only country in Europe where the pioneer of the process was a native. William Caxton – a middle-aged amateur with a background in the woollen trade – came to printing in 1471 when he translated Lefèvre’s Recueil des histories de Troye, which he printed himself having first observed the craft in Cologne. Back in England he set up a press in the precincts of Westminster Abbey, secured a royal warrant, and in 1477 issued the first book printed in this country. Although he specialised in expensive, publications he was not England’s best printer, but he was certainly the first. Caxton is immortalised in a stained-glass window at Stationers' Hall.

Wynkyn de Worde, 1479 (est)–1535

Printer, Fleet Street, London

When Caxton died his business was taken over by his assistant, Wynkyn de Worde. Whereas Caxton was a scholar with royal connections, Wynkyn de Worde was primarily a businessman who concentrated on producing cheap books for the many rather than costly publications for the few. Wynkyn de Worde was a popular printer of small works at modest prices, and he satisfied the market for school books, Latin grammars, primers and liturgies, printing over 700 works between 1492 and 1532. Wynkyn de Worde was not a particularly good printer, but he was certainly one of the most industrious and the first to popularise the products of the press. Pictured is de Worde's Shepherds' Calendar, a guide to spiritual and physical health.

When Caxton died his business was taken over by his assistant, Wynkyn de Worde. Whereas Caxton was a scholar with royal connections, Wynkyn de Worde was primarily a businessman who concentrated on producing cheap books for the many rather than costly publications for the few. Wynkyn de Worde was a popular printer of small works at modest prices, and he satisfied the market for school books, Latin grammars, primers and liturgies, printing over 700 works between 1492 and 1532. Wynkyn de Worde was not a particularly good printer, but he was certainly one of the most industrious and the first to popularise the products of the press. Pictured is de Worde's Shepherds' Calendar, a guide to spiritual and physical health.

Agnes Campbell, 1637–1716

Printer, Edinburgh

Agnes Campbell was one of the few women printers and book merchants in the early modern period. She inherited her business in 1678 following the death of her husband, Andrew Anderson. Agnes held the title of king’s printer, was typographer to the burgh and university of Edinburgh and used the imprint ‘Heirs of Andrew Anderson’. Campbell’s press was the largest in Scotland and the largest Presbyterian press in Edinburgh. Even in 1678 she had no fewer than 16 apprentices. As a royal printer she was exempt from import and export customs and excise dues and taking advantage of these exemptions, she traded widely in books and paper, she also acted as moneylender to numerous book traders in Scotland, England and Ireland.

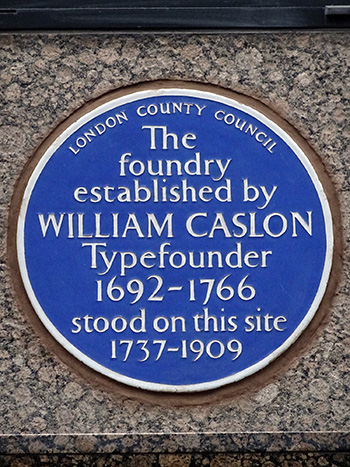

William Caslon, 1692–1766

Type-founder, London

William Caslon, England’s first native type-founder of note was originally an engraver of ornamental guns. In 1720, he added the cutting of typographic punches to his repertoire. Caslon turned to punch cutting at a fortuitous time. English type-founding was poor in design and inferior in manufacture and any type of any quality had to be imported from mainland Europe. With his cutting of the famous ‘Caslon’ typeface, the former gun-lock engraver rescued English type-founding from the mire into which it had sunk, gave the country a range of letters equal to anything available on the Continent, and spawned a dynasty of founders whose name continues to this day.

William Caslon, England’s first native type-founder of note was originally an engraver of ornamental guns. In 1720, he added the cutting of typographic punches to his repertoire. Caslon turned to punch cutting at a fortuitous time. English type-founding was poor in design and inferior in manufacture and any type of any quality had to be imported from mainland Europe. With his cutting of the famous ‘Caslon’ typeface, the former gun-lock engraver rescued English type-founding from the mire into which it had sunk, gave the country a range of letters equal to anything available on the Continent, and spawned a dynasty of founders whose name continues to this day.

John Baskerville, 1707–1775

Type-founder, Printer, Birmingham

Baskerville, with its well-considered design and elegant proportions is one of the world’s most widely used and influential typefaces. It was created by John Baskerville, typographer, printer and industrialist; an Enlightenment figure with a worldwide reputation who changed the course of type design. Baskerville was the ‘complete printer’ who considered all aspects of the craft by experimenting with casting and setting type, improving the construction of the printing press, developing a new kind of paper and refining the quality of inks. His typographic experiments put him ahead of his time, had an international impact and did much to enhance the printing and publishing industries of his day.

Baskerville, with its well-considered design and elegant proportions is one of the world’s most widely used and influential typefaces. It was created by John Baskerville, typographer, printer and industrialist; an Enlightenment figure with a worldwide reputation who changed the course of type design. Baskerville was the ‘complete printer’ who considered all aspects of the craft by experimenting with casting and setting type, improving the construction of the printing press, developing a new kind of paper and refining the quality of inks. His typographic experiments put him ahead of his time, had an international impact and did much to enhance the printing and publishing industries of his day.

Luke Hansard, 1752–1828

Printer, Covent Garden, London

Luke Hansard was printer to the House of Commons for over 50 years, and his printing house was the largest in London, employing 200 men and executing all Parliament’s printing. Hansard printed the Journal a daily record of the decisions of the Commons and it remains a lasting monument to his skill as a printer and knowledge of parliamentary procedure. A sure typographer, Hansard was skilled in reducing the complex, cumbersome matter of debates and committee reports to legible and intelligible pages, and an accomplished manager who combined meticulous attention to detail with a talent for hard work that made him indispensable to Parliament for half a century.

Charles Stanhope, third Earl Stanhope, 1753–1816

Inventor of the first iron press, Chevening, Kent

Charles Stanhope was a politician and inventor with an interest in printing technology. He devised a new printing press which bore his name, developed a form of stereotyping and introduced a system of logotypes. His printing press, the first to be constructed wholly from iron, had a novel lever and screw motion and a platen the full size of the bed thus enabling an impression to be made in one pull compared with two pulls on traditional presses. A labour-saving invention, the Stanhope Press was a considerable improvement on its predecessors and the most successful printing press of its era, which was used for the printing of The Times (more details, p50).

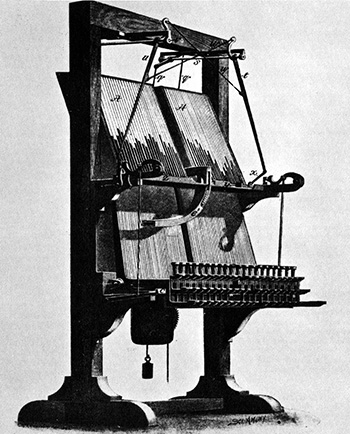

Dr William Church, 1778–1863

Inventor of the first type composing and casting machine, Birmingham

Between 1822 and 1850, William Church registered no fewer than 15 patents. His inventions ranged from steam carriages to bedsteads, and included three patents for printing machines and other inventions relative to printing: a press for printing and delivering sheets in a pile; a contraption for numbering and printing railway tickets; and a type composing and casting machine, thought to be the first of its kind. The London Journal of Arts & Sciences described Church’s invention as being at “the front of those valuable and useful inventions which adorn the present age”. Church was certainly ahead of his time and his composing and casting machine was a precursor to both the Linotype and Monotype machines.

Between 1822 and 1850, William Church registered no fewer than 15 patents. His inventions ranged from steam carriages to bedsteads, and included three patents for printing machines and other inventions relative to printing: a press for printing and delivering sheets in a pile; a contraption for numbering and printing railway tickets; and a type composing and casting machine, thought to be the first of its kind. The London Journal of Arts & Sciences described Church’s invention as being at “the front of those valuable and useful inventions which adorn the present age”. Church was certainly ahead of his time and his composing and casting machine was a precursor to both the Linotype and Monotype machines.

George Baxter, 1804–1867

Colour printer, Clerkenwell, London

Baxter developed a colour printing process which brought him international fame. In 1829 he produced his first coloured print, Butterflies, and in 1834 his coloured plates for Feathered Tribes of the British Islands were greeted with widespread acclaim. In 1836 he received a royal patent for his innovative technique, which combined an engraved metal plate with as many as 20 engraved wooden blocks, each printed in a separate colour. The prints united quality and cheapness and were produced in vast numbers. For 25 years Baxter dominated colour printing, also branching out into decorated music sheets, notepaper, pocket-books, and needle cases. He claimed to have produced 20 million prints by the end of his career.

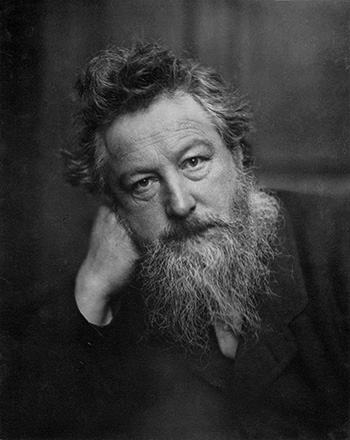

William Morris, 1838–1896

Kelmscott Press, Hammersmith, London

William Morris was a leading exponent of the arts and crafts movement. He was a printer whose publications were produced as protests against what he perceived to be the poor standards of Victorian typography, caused by new mechanical methods of production. As a socialist, Morris believed everyone was entitled to well-made things, and he produced his books using the same hand-processes and craft principles as the early printers. Morris’ beautiful but expensive books were made for effect not reading; as showcases, not exemplars. His books were typographic throwbacks, and yet they marked a revival in fine printing, because Morris had demonstrated that fine craftsmanship and careful typography was not a lost art.

William Morris was a leading exponent of the arts and crafts movement. He was a printer whose publications were produced as protests against what he perceived to be the poor standards of Victorian typography, caused by new mechanical methods of production. As a socialist, Morris believed everyone was entitled to well-made things, and he produced his books using the same hand-processes and craft principles as the early printers. Morris’ beautiful but expensive books were made for effect not reading; as showcases, not exemplars. His books were typographic throwbacks, and yet they marked a revival in fine printing, because Morris had demonstrated that fine craftsmanship and careful typography was not a lost art.

Horace Hart, 1840–1916

Printer, Oxford

Horace Hart was a biographer and Controller of Oxford University Press (OUP) and he did much to raise the standard of work both at OUP and in printing houses around Britain. Hart was interested in both the technology of printing and the historical and literary side of the business, which made him particularly suited to work at OUP. His major work, Rules for Compositors and Readers, originated as a compilation of the best practices and standards he had observed throughout his career. Issued privately in 1893, and originally intended as house rules for Oxford printers, demand was so great that Hart published the booklet in 1904 and it became the accepted authority on English grammar, punctuation, and disputed spellings and has been indispensable to all printing professionals ever since.

George W Jones, 1860–1942

Printer, type designer, London and Watford

George W Jones was a polymath of print. As an educationalist he established British Typographica, a nationwide precursor to the schools of printing. As a publisher Jones produced the first edition of The British Printer and, from 1891, Printing World. As a printer Jones pioneered Linotype and Miehle usage, composing Printing World totally on the Linotype as early as 1900 and using the Miehle to produce the first three-colour book in Britain in 1901. As a type designer Jones created Venezia for Stevens Shanks and Granjon, Estienne, Georgian and Baskerville for Linotype, becoming a printing advisor to Linotype in 1921. Some have described Jones as the best all-round printer that Britain has ever produced.

Eric Gill, 1882–1940

Printer, type designer, Ditchling, East Sussex

Eric Gill was an artist, craftsman, social critic, letter-cutter and a type designer of genius. He was also a printer and co-founded, with Henry Pepler, the St Dominic’s Press in 1915 where he produced wood engravings and lettering. In 1924 he produced a series of engravings for the Golden Cockerel Press; the best remembered of which is the Four Gospels (1931), printed from type expressly designed by him for the press. With his son-in-law René Hague, he established a private press at his home where, in 1931, he printed his controversial essay, ‘Typography’. His typefaces, issued by Monotype, include Perpetua (1925), Gill Sans (1927), Joanna (1930), and Bunyan (1934), and are still in use today.

Leonard Jay, 1888–1963

Teacher, printer, Birmingham

Leonard Jay was a teacher par excellence who influenced the outlook of a whole generation of printers and made a significant contribution to printing education in the 20th century. Head of the Birmingham School of Printing, Jay had the rare courage to teach the new idea that mechanical composition could produce excellence in printing as effectively as hand composition. Jay made craftsmen out of others by teaching them to discriminate and to reject whatever was substandard in design or execution. Jay’s most important legacy was those boys who trained under him and who took their learning into printing businesses across the country, raising standards in the industry.

Stanley Morison, 1889–1967

Type designer, scholar, London

Stanley Morison was Britain’s greatest authority on letter design, a reputation won by his role as typographical adviser to the British Monotype Corporation from 1922-54. A dozen typefaces made to his specifications, some typographic revivals, some new faces drawn by artists including Eric Gill and Berthold Wolpe, became commonly used around the world. Morison’s writings – over 200 books, articles, and reviews – guided standards in British book production. His final writing, First principles of typography, has been frequently reprinted, and was translated into six languages during Morison’s lifetime. Morison’s role as typographical advisor to The Times for over 30 years made him known to a wider public.

Beatrice Warde, 1900-1969

Publicity Manager, Monotype, Surrey

Beatrice Warde was a middle-class American who moved to Britain as a young woman in 1925 and is best known for her work as Publicity Manager to the British Monotype Corporation. A lone female voice in the male dominated British printing industry, she devoted herself to “spreading ideas about good typography... to the widest possible audiences” with astonishing results. Her public lectures and published writings on typographic history, theory and practice, are now part of the typographic canon, the most enduring of which is ‘The Crystal Goblet’, or printing should be invisible. Through her work Warde transcended traditional boundaries and was widely regarded as the ‘First Lady of Typography.’

Barbara Theresa Cumming, [name in religion Hildelith Cumming], 1909–1991

Printer, Stanbrook Abbey, Worcestershire

Hildelith Cumming was nun, musician and printer at the Stanbrook Abbey Press 1955-1990. Under her guidance Stanbrook became one of the leading private presses, renowned for the quality of its book design and press work. Cumming’s collaborated with many leading printers and typographers, most notably Jan van Krimpen whose types were used in the majority of Stanbrook’s fine books from 1958 onwards. The combination of handmade papers and distinguished types, with the calligraphy and decorations of Margaret Adams, characterised much of the Cumming’s output which included 80 titles between 1956 and 1988. Cumming’s was a first-rate private press printer, but these achievements were expressions of her Benedictine vocation, to which she devoted the major part of her life.

John Crosfield, 1915–2012

Crosfield Electronics, Hemel Hempstead, Hertfordshire

John Crosfield was inventor, entrepreneur, and pioneered the application of electronics to colour printing. In 1947, he founded Crosfield Electronics, which designed and manufactured control equipment for presses to ensure the register of four-colour printing. Known as the Autotron, it was adopted by printers world-wide. Crosfield also lead the introduction of colour scanning, phototypesetting and the automated composition of pages incorporating pictures and text, developing the first colour scanner, the Scanatron, in 1959. In 1975 Crosfield Electronics launched the Magnascan 550, the world’s first digital scanner controlled by computer with all the separation and correction process performed in the computer, followed closely by the first electronic page composition system.

Victor Watson, (Mr Monopoly) 1928–2015

Chairman of Waddingtons, Leeds

In 1951, Victor Watson joined the family-run John Waddington Ltd, which his grandfather had acquired when it was a struggling provincial print firm and transformed it into a market leader. Watson was chairman of Waddingtons from 1977 to 1993, during which time he oversaw the launch and re-launch of games including Monopoly and Cluedo as well as the continued production of No 1 playing cards, a legacy from the first world war. Watson’s own time at the helm was turbulent and as the company grew, he fought off takeover bids from Robert Maxwell’s British Printing & Communications Corporation. In 2007, Watson received the BPIF’s first award for Outstanding Contribution to the Printing Industry. An annual award for outstanding achievement by young people in the industry is made in his name to this day.

In 1951, Victor Watson joined the family-run John Waddington Ltd, which his grandfather had acquired when it was a struggling provincial print firm and transformed it into a market leader. Watson was chairman of Waddingtons from 1977 to 1993, during which time he oversaw the launch and re-launch of games including Monopoly and Cluedo as well as the continued production of No 1 playing cards, a legacy from the first world war. Watson’s own time at the helm was turbulent and as the company grew, he fought off takeover bids from Robert Maxwell’s British Printing & Communications Corporation. In 2007, Watson received the BPIF’s first award for Outstanding Contribution to the Printing Industry. An annual award for outstanding achievement by young people in the industry is made in his name to this day.

Bob Gavron CBE 1930–2015

Chairman of St Ives Group, 1964-1993

It’s more than 20 years since Bob Gavron retired from St Ives, the print group he created after taking over a failing print business, and which was wildly successful under his stewardship. With a mind brilliant enough to be called to the Bar, but with the nous to know that his true calling lay elsewhere. Gavron was a man of prodigious talents, and one of his most important was recognising and nurturing the abilities of others and inspiring them to do their best. His printing odyssey resulted in the creation of the most highly respected and successful print group of its day and made him a multimillionaire. He became a Labour peer in 1999. When Gavron died in 2015 aged 84 there was an outpouring of respect and admiration for his many achievements. Gavron’s legacy lives on today among those who were lucky enough to know him.

It’s more than 20 years since Bob Gavron retired from St Ives, the print group he created after taking over a failing print business, and which was wildly successful under his stewardship. With a mind brilliant enough to be called to the Bar, but with the nous to know that his true calling lay elsewhere. Gavron was a man of prodigious talents, and one of his most important was recognising and nurturing the abilities of others and inspiring them to do their best. His printing odyssey resulted in the creation of the most highly respected and successful print group of its day and made him a multimillionaire. He became a Labour peer in 1999. When Gavron died in 2015 aged 84 there was an outpouring of respect and admiration for his many achievements. Gavron’s legacy lives on today among those who were lucky enough to know him.