It turns out that the death of the book has indeed been much exaggerated. Rather than being swept away on an unstoppable tide of cheap e-books, sales of physical, printed books rose for the second year running, by 7% in 2016, while sales of e-books actually fell, by 4%.

Speaking at the conference that preceded the event, Nielsen research director Steve Bohme said: “The good news for books was that purchases grew last year, spending was up by 6% and most of that growth was driven by printed books. So yes, we’re seeing a bit of a revival of the printed book over the last couple of years.”

Some of the increase in physical book sales has been driven by the continuing popularity of adult colouring books, while blockbuster bestsellers (such as Paula Hawkins’ Girl on a Train) also create a spike in sales. What’s clear is that proper, printed books have an enduring appeal based on the sort of print attributes that have been well-documented in the pages of PrintWeek, including format, cover and paper type, and print finishes. As the Publishers Association has noted: “Readers take pleasure in a physical book that does not translate well on to digital.”

A glance at the bestseller charts also shows that online stars such as Joe Wicks and Zoella with their huge Twitter, YouTube and Instagram followings (Zoella was named in top spot in Heat magazine’s recent list of the most powerful social media stars) have ended up being phenomenally successful in the analogue world of printed products, generating enormous sales of physical books. Wicks’ Lean in 15 series sold more than 1.5 million copies last year. And many of these books are purchased by or for the sort of younger millennial demographic that can typically be found glued to their smartphones.

“There’s been so much rubbish talked over the years about the death of the book and I’ve never believed it,” says David Taylor, group managing director at Lightning Source UK, part of book distribution giant Ingram.

Challenging market

However, despite the recent positive news, UK book printers still operate in an extremely challenging and competitive environment, with competitors from continental Europe and the Far East producing large volumes of books destined for the UK. Witness the fact that within the past five years book specialists Butler Tanner & Dennis, MPG Books, and Berforts Information Press have all shut down.

“The market is not easy as recent news of the demise of various companies has shown, a solid financial base and continual investment has been the key for us,” says Helen Kennett, managing director at Dorset’s Henry Ling.

And there is a mixed picture across trade publishing and the STMA (scientific, technical, medical and academic) markets.

“If you review the market data, it would suggest that trade hardbacks and paperbacks are showing a decline of 3% in the coming year, and 8% within the STMA market,” explains CPI Group divisional general manager Alison Kaye. “Year-to-date we have seen a 9% increase in trade hardbacks and a 14% increase in paperbacks, including special sales. Our STMA volumes are flat, due to a reduction in overall print runs, but the number of ISBNs produced has increased.”

Kaye’s assessment backs up the trend among publishers towards the production of multiple smaller orders rather than one large print run that is then held in stock.

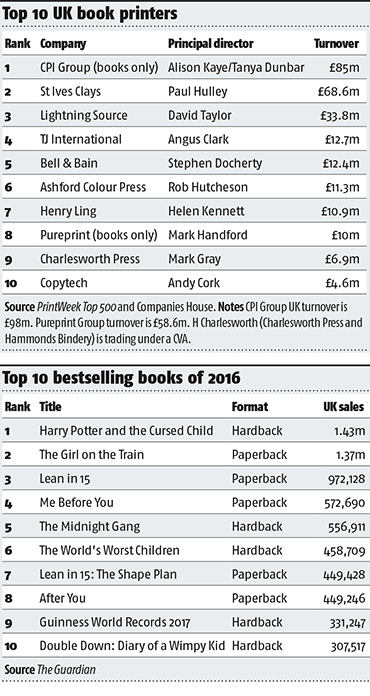

CPI sits at the top of our league table along with St Ives Clays, as by far the biggest high-volume book printers in the UK. As such any wrestling over large contracts from the major trade publishers tends to take place between these two arch-rivals.

In 2015 Clays won a sole supplier deal to print all the Penguin Random House monochrome work, which had previously been split between the two groups. That subsequently resulted in the closure of CPI’s Cox & Wyman facility. While earlier this year we learned that CPI had won the HarperCollins contract currently held by Clays, which will in turn involve job losses at its Bungay facility.

Further significant happenings at the top of our chart also seem likely, with much talk about a likely change of ownership at the venerable book printer after St Ives announced a strategic review of its remaining print operations, pledging to take “decisive action”, which could potentially trigger a complete sell-off of its print interests.

More happily for the company, Clays also printed the bestselling book of 2016, JK Rowling et al’s Harry Potter and the Cursed Child. Despite being a script the extent of Harry Potter fandom ensured it sold an astonishing 1.4 million copies in hardback last year.

St Ives described it as “the biggest single book launch in the UK and US for 10 years”, with a huge behind-the-scenes logistical operation taking place to ready the necessary quantities of books ahead of publication, including distribution to more than 50 retail destinations.

Such mega-blockbusters may grab the headlines, but they are the exception, rather than the norm, as Lightning Source’s Taylor explains. “There will always be books, like those by JK Rowling or Wilbur Smith, that have a place in the book trade whereby it makes sense to print and carry inventory. But the vast majority of books sell in very small quantities,” he asserts.

Lightning Source has based its entire business on a print-on-demand model, to the extent that Taylor says the firm’s average run length is a mere 1.5 copies. And these small runs are proving to be big business for the company, with UK sales jumping by almost 22% in 2015 to £33.8m.

“We are the genuine print-on-demand article,” he says. “The single copy thing is so important, and is one of the real reasons for our success. It has allowed publishers over the past 20 years to change their business model completely – they don’t need to print a book before they sell it.”

As Taylor notes, the old publishing model of printing a high number of copies in order to achieve a suitably low unit cost, and then keeping those books in stock, is fraught with the potential for error.

“They always get that wrong, they either print too many or they don’t print enough and run out. The reason Lightning Source is so successful is that it’s a global distribution system that allows publishers to change the shape of their business. They don’t need to have their capital tied up in warehouses.”

Lightning Source even produces single-copy hardbacks, and Taylor says the “vast majority” of publishers have now embraced print-on-demand, including academic and trade publishers. “You may well have bought a book that was manufactured on-demand by us and not known it – there’s no difference.”

And this kind of model, involving ease of printing and known cost of production, has also helped spur entirely new publishing models, such as crowdfunding publishing platform Unbound (www.unbound.com), which has now published more than 200 books that it believes would never have made it to market otherwise.

The desire to reduce stockholding and be more responsive has also filtered through into the high-volume end of the market as CPI’s Kaye confirms. She reports growing publisher demand for services such as print-on-demand, automatic stock replenishment and distributive print through CPI’s Global Print Solutions offering.

“Newer models are beginning to firmly establish themselves, such as zero inventory and managed inventory, with the printer taking control of storage, fulfilment and distribution, particularly in the STMA/journal markets,” she notes. “With these workflows, comes an increasing demand of speed to market, and at its extreme, we see zero inventory product turnarounds from order to ship in 48 hours. To simply deliver ink on paper, is quite rightly, not enough.”

Ling’s Kennett concurs: “We are seeing a trend for lower print runs, little or no stock holding and therefore an increase in POD for both limp and cased books.”

Key to it all is technology and the right IT systems, which Kaye describes as “critical”. “One thing is certain, IT connectivity with some publishers is becoming as important a part of doing business as delivering the printed product.”

As such, software and workflow technology is increasingly the ‘special sauce’ that can differentiate an offering. “There’s nothing unusual in the kit we use, what is special is the routing software and the linkages to distribution,” Taylor explains.

Another area of on-demand book printing, and one that does not make it into the official bestseller charts, is the personalised book phenomena made popular by publishers such as Lost My Name, Penwizard, and Petlandia. Lost My Name, for example, trumpeted that it had produced its millionth book last year.

Work of this nature is among the portfolio of book products produced by PrintWeek’s reigning Book Printer of the Year, Pureprint, which has a range that spans luxury coffee table volumes to digitally-produced personalised books.

“We specialise in bespoke and personal books that take advantage of the wide range of materials and format that physical books can explore, to produce publications that creatively support the values and qualities of the subject,” says director Richard Owers. “We also produce personalised books which are viewed and ordered through web shops were we produce and are fulfilling unique orders of one to over 100 countries.”

And it’s also worth noting that despite the high-profile demise of Butler Tanner & Dennis, a number of colour book printing exponents still exist in the UK. Some might even be described as flourishing.

“We’re very busy, probably 15%-20% up on last year on work coming in,” reports Stephen Docherty, managing director at Glasgow’s Bell & Bain. “We do a tremendous amount of colour books now.”

Adding firepower

While digital kit investments have tended to be more attention-grabbing, Docherty credits the company’s new four-back-four KBA Rapida 145 and Muller Martini Diamant MC35 case binder with providing “tremendous firepower” to allow the firm to turnaround colour book work quickly. “We are producing case-bound titles within four-to-eight days. My next project is to integrate our binding lines so we can be constantly binding without stopping the flow of books.”

And in Wales Gomer Press commercial manager Martin Koffer reports “a bit of a revival in books as objects”.

“We are doing a lot of binding in nice cloths, with nice end papers and nice foiling. Colour coffee table books is our particular niche,” Koffer says.

Over the last five years Gomer Press has quietly built up its offering for London galleries and fine art institutions. “BT&D were not the last full-service book production house in the UK, although people talked like they were at the time of their demise. A lot of people say ‘oh, so there is a UK option...’,” he adds.

And while there’s no escaping the fact that many books purchased in the UK are still printed overseas, a number of factors are working in favour of local production, with widespread reports of increased interest in so-called re-shoring of work in the wake of the fall in the value of the pound due to Brexit. The trend towards more frequent, smaller print runs also lends itself to local production. Is it actually happening?

One book printer jokes that given the size of the book printing industry in the UK nowadays, “there are not many of us left so it doesn’t take much to make us all busy”.

The serious flip side to this is a very real boost to business. “There’re definitely a couple of people where we’ve been knocking on their door before and they were not interested, but now they have come back to us,” Koffer reports, “We have gained work that would have been produced in the Far East before, so that’s positive.”

The benefits are, of course, “slightly negated by the increase in paper prices”, as David Martin, sales director at Martins The Printers in Berwick-upon-Tweed points out. But he remains optimistic about the opportunities around re-shored work. “The work is coming back differently. Run lengths are coming down, and turnarounds are faster, and that trend will continue.

“People might have produced 10,000 in China, and it’s now down to 5,000 and then coming down again to 2,000. That trend is good for us. Hopefully we can stay around long enough to see it come back!” he quips.

“At the London Book Fair it was quite enlightening, everybody was interested in talking about printing in the UK and I found that unusual and also very welcome. It’s just about grabbing the opportunity as it comes by.”

The $60m dollar question, then, as Martin puts it, is whether such work will flow straight back again to overseas producers should the exchange rate shift in the other direction. However, combined with the trends for timeliness of production, on-demand printing and reduced stock holding, there are factors working in favour of UK book printers that should mean the sector can look forward to its next chapter with a degree of confidence.